ISSUE1684

- Mark Abramowicz, M.D., President has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

- Jean-Marie Pflomm, Pharm.D., Editor in Chief has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

- Brinda M. Shah, Pharm.D., Consulting Editor has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

- Michael Viscusi, Pharm.D., Associate Editor has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

- Explain the current approach to treatment of opioid use disorder.

- Discuss the pharmacological options available for treatment of opioid use disorder and compare them based on their efficacy, safety, potential drug interactions, and availability.

- Determine the best course of treatment for an individual patient with opioid use disorder.

- Maintenance pharmacotherapy is the standard of care.

- Maintenance treatment with methadone has been shown to reduce mortality, but respiratory depression and drug interactions are a concern.

- Buprenorphine is the maintenance treatment of choice for most patients. It is safer than methadone, can be prescribed in an outpatient setting, and at higher doses appears to be similarly effective.

- Extended-release naltrexone is an alternative for highly motivated patients who do not have access to buprenorphine or methadone or do not want to take an opioid and for those who also have alcohol use disorder. Naltrexone has not been conclusively shown to reduce mortality.

- In pregnant or breastfeeding women, maintenance treatment with methadone or buprenorphine is recommended.

- Naloxone is the drug of choice for emergency treatment of opioid overdose. The FDA has approved over-the-counter sale of naloxone nasal sprays.

|

Outline Treatment of Opioid Overdose References Tables |

Opioid use disorder is a chronic, relapsing disease with physical and psychiatric components. It is associated with economic hardship, social isolation, incarceration, increased rates of blood-borne infections such as HIV and viral hepatitis, adverse pregnancy outcomes, and increased mortality. According to the NIH, there were 80,411 deaths involving an opioid in the US in 2021, more than in any previous year.1 Several guidelines on the management of opioid use disorder are available; all recommend maintenance pharmacotherapy as the standard of care.2-5

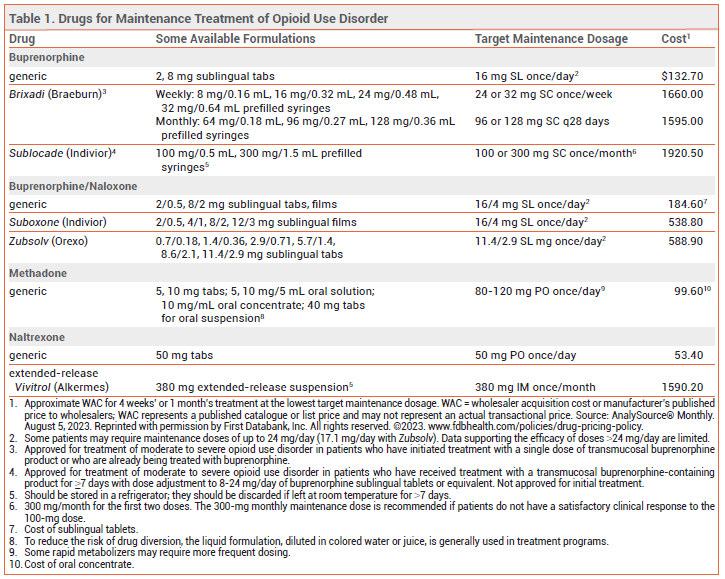

METHADONE — A synthetic mu-opioid receptor agonist, methadone suppresses opioid cravings and blocks the euphoric effects of other opioids. It has a slow onset of action and a long, variable elimination half-life. At high doses, it induces cross-tolerance to other opioid agonists. Patients tolerant to other opioid agonists, however, may have incomplete cross-tolerance to methadone.6

Availability – Methadone is classified as a schedule II controlled substance (highest potential for abuse; recognized medical use). In the US, methadone maintenance treatment for opioid use disorder is only available through government-licensed opioid treatment programs, which offer supervised administration of the drug. Methadone is available in oral tablets, tablets for oral suspension, an oral solution, and an oral concentrate. To reduce the risk of drug diversion, methadone treatment programs usually do not dispense the tablet formulation.7

Efficacy – Methadone maintenance therapy can improve treatment retention, productivity, and social engagement and decrease crime rates, injection risk behaviors, mortality rates, and the spread of blood-borne infections such as hepatitis C and HIV.8-12 Use of higher doses of methadone (≥100 mg/day) in patients with opioid use disorder and HIV infection has been associated with increased adherence to antiretroviral therapy, lower viral loads, and higher CD4+ T-cell counts.13

Safety – The risk of mortality is highest in the first weeks after starting or stopping methadone treatment.14 The drug accumulates during induction; it takes 4-7 days to achieve steady state. In overdosage, or if the dose is increased too rapidly, methadone can cause sedation and respiratory depression. The respiratory depressant effect of methadone peaks later and lasts longer than that of buprenorphine and other opioid agonists, and it persists longer than the analgesic effect of the drug. Tolerance can be lost quickly; if a patient misses maintenance doses, the dose should be reduced and retitrated to avoid development of life-threatening respiratory depression.

Methadone can prolong the QT interval and cause arrhythmias such as torsades de pointes, particularly in patients taking high doses (>120 mg/day) or other drugs that prolong the QT interval, and in those with congenital long QT syndrome or a history of QT-interval prolongation.15 Hypokalemia and cocaine use may also contribute to acquired long QT syndrome.

Drug Interactions – Methadone is a substrate of CYP3A4 and CYP2B6; inhibitors of these isozymes, such as ritonavir, cobicistat, or clarithromycin, can increase serum concentrations of methadone, and inducers, such as rifampin, carbamazepine, or phenytoin, can reduce them.16 Concurrent use of methadone and other drugs that prolong the QT interval should be avoided if possible.15 As with any opioid, concomitant use of methadone with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), tricyclic antidepressants, or other serotonergic drugs can rarely result in serotonin syndrome. Concurrent use of methadone and benzodiazepines or other sedating drugs can cause additive CNS depression.

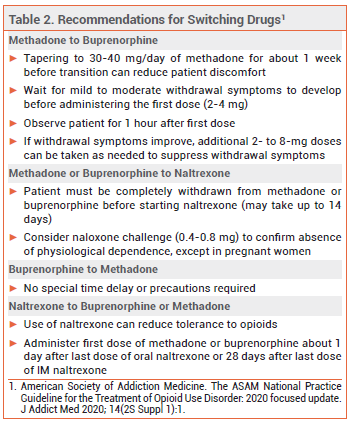

Dosage and Administration – In patients with low or no opioid tolerance (e.g., those transitioning from naltrexone), an initial methadone dose of 2.5-10 mg is appropriate. Federal law prohibits administration of an initial methadone dose >30 mg or a total first daily dose >40 mg, unless the physician documents that 40 mg did not suppress opioid abstinence symptoms.17 Because methadone has a long half-life, the dosage should be titrated cautiously based on the patient’s response; a typical timeline might be 10 mg every 5 days. For most patients, a maintenance dose of 60-120 mg/day can suppress cravings and block the euphoric effects of other opioid agonists.18

View the Comparison Table: Some Drugs for Maintenance Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder

BUPRENORPHINE — A mu-opioid receptor partial agonist and kappa-opioid receptor antagonist, buprenorphine is used alone and in combination with the opioid antagonist naloxone (Suboxone, Zubsolv, and generics).19-21 Taken sublingually, naloxone is poorly absorbed and generally has no clinical effects; combining it with buprenorphine is intended to deter intravenous or intranasal abuse. Two extended-release buprenorphine formulations (Brixadi, Sublocade) are FDA-approved for subcutaneous treatment of moderate to severe opioid use disorder.22,23

Availability – Buprenorphine is classified as a schedule III controlled substance (less potential for abuse than schedule II; recognized medical use). In the US, federal regulations no longer require prescribers to have a DATA-waiver (X-waiver) to prescribe buprenorphine for opioid use disorder in an outpatient setting.24 Brixadi and Sublocade are only available through a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program.22,23

Efficacy – Buprenorphine improves treatment retention and reduces illicit opioid use. It appears to be at least as effective as methadone in reducing mortality.12,14 Office-based buprenorphine/naloxone maintenance treatment has been shown to improve abstinence rates, occupational stability, and psychosocial outcomes.25

Subcutaneous buprenorphine should reduce the risks of treatment nonadherence and drug diversion compared to sublingual formulations, but it is much more expensive.

Safety – Even without naloxone, buprenorphine is safer than methadone because it has a ceiling on its respiratory depressant effect. As a partial agonist, it also has a lower abuse potential than methadone; the presence of naloxone may further reduce the abuse potential of buprenorphine.

Buprenorphine has a greater affinity for opioid receptors than full opioid agonists such as fentanyl and can displace them, causing opioid withdrawal.

Buprenorphine is less likely than methadone to cause cardiac adverse effects. In a retrospective analysis of about 5 million adverse drug events reported to the FDA over 42 years, events mentioning methadone, but not those mentioning buprenorphine, were disproportionately likely to involve QT-interval prolongation, ventricular arrhythmia, or cardiac arrest.26

Hepatic impairment reduces naloxone clearance to a greater extent than it does buprenorphine clearance. Use of buprenorphine/naloxone in patients with severe hepatic impairment can lead to withdrawal symptoms when treatment is started and may decrease the efficacy of buprenorphine maintenance.

Injection-site reactions can occur with subcutaneous administration of buprenorphine.

Drug Interactions – Concurrent use of buprenorphine and benzodiazepines or other sedating drugs can result in additive CNS depression. Buprenorphine is metabolized primarily by CYP3A4; use with a 3A4 inducer can decrease buprenorphine serum concentrations and use with a 3A4 inhibitor can increase them. Buprenorphine is also a substrate of P-glycoprotein (P-gp); concomitant use of inhibitors of P-gp could increase buprenorphine serum concentrations.16 Use of an opioid with serotonergic drugs such as SSRIs may result in serotonin syndrome, though the risk is lower with buprenorphine than it is with directly serotonergic opioids such as methadone.

Buprenorphine can interfere with the analgesic efficacy of full opioid agonists, but current guidelines recommend that patients taking the drug who require surgery continue taking it, with full agonist opioids added as needed.27

Dosage and Administration – The risk of serious withdrawal symptoms can be reduced by withholding buprenorphine treatment until the patient is experiencing mild to moderate opioid withdrawal symptoms (Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale score ~11-12)28 and by using a low initial dose (typically 2-4 mg of Suboxone or equivalent; some clinicians use as little as 0.5 mg when transitioning from methadone or fentanyl29). The daily dose should be uptitrated, usually in increments of 2-8 mg, to 16 mg/day. Some patients may require higher maintenance doses (16-24 mg/day). Data supporting increased efficacy with doses >24 mg/day are limited.30

Brixadi can be given once weekly or once monthly; it can be started after a single sublingual dose of buprenorphine and can be stored at room temperature. Sublocade is injected once monthly and can be started after 7 days of treatment with sublingual buprenorphine; it should be stored in a refrigerator but can be left at toom temperature up to 7 days before administration.

NALTREXONE — The mu-opioid receptor antagonist naltrexone is available as a once-daily oral tablet and as a once-monthly extended-release microsphere suspension given by intramuscular (IM) injection (Vivitrol). It is not addictive or readily abused, and tolerance to its effects does not develop with long-term use. Both oral and extended-release IM naltrexone are also FDA-approved for treatment of alcohol use disorder.31

Availability – Naltrexone is not a controlled substance, and there are no special restrictions on its prescription.

Efficacy – Adherence and outcomes are better with once-monthly IM naltrexone than with the oral formulation. IM naltrexone has been shown to improve abstinence rates and retention in treatment programs and to reduce cravings and relapse to physiological dependence.32,33 In a 24-week, open-label study in 570 patients, treatment failure during induction occurred significantly more often with once-monthly IM naltrexone than with sublingual buprenorphine/naloxone, but among those who were successfully inducted, the two treatments were similar in efficacy and safety.34 In a 12-week, open-label study in 159 patients in Norway, abstinence and treatment retention rates with IM naltrexone were noninferior to those with sublingual buprenorphine/naloxone.35 Whether use of IM naltrexone can reduce the risk of death remains to be determined; in one meta-analysis of 30 cohort studies, patients treated with the drug had lower rates of death from overdose and from all causes.36

In a meta-analysis of 13 studies, oral naltrexone was not more effective than placebo, nonpharmacologic treatment, benzodiazepines, or buprenorphine in reducing opioid use, and treatment retention was poor.37 Oral naltrexone was more effective than placebo in sustaining abstinence in studies where patients were legally mandated to take the drug.32,37,38

Safety – Naltrexone is generally well tolerated. Adverse effects of IM naltrexone have included injection-site reactions, hepatic enzyme elevations, nasopharyngitis, insomnia, headache, nausea, and toothache. Depressed mood and suicidality have occurred rarely; a causal relationship has not been established. Hepatotoxicity has been reported with use of naltrexone, but it is also associated with opioid and alcohol use disorders themselves. Naltrexone can reduce tolerance to opioids; patients who relapse after receiving naltrexone may be at greater risk of a serious, potentially fatal opioid overdose.

Drug Interactions – Naltrexone blocks the effects of opioids, including opioid-derivative antidiarrheals and antitussives.39 It should not be used in patients taking an opioid for treatment of pain. Oral naltrexone should be stopped 72 hours before and IM naltrexone 30 days before elective surgery.

Dosage and Administration – Administration of naltrexone to a patient with physiological opioid dependence can precipitate a severe opioid withdrawal syndrome; patients should be free of dependence for at least 7 days before naltrexone is started. A naloxone challenge can be used to confirm the absence of physiological opioid dependence. Patients starting treatment with oral naltrexone should receive an initial dose of 25 mg. If withdrawal symptoms do not occur, a maintenance dosage of 50 mg once daily can be given.

Vivitrol should be given as a deep intragluteal injection in alternating buttocks every 4 weeks or once monthly. The drug should be stored in a refrigerator, but it can be left unrefrigerated for up to 7 days as long as it is not exposed to temperatures >77°F (25°C).

ALTERNATIVES — Limited data suggest that 24-hour extended-release oral morphine (off-label) may be effective for maintenance treatment of opioid use disorder. Morphine may be better tolerated and more effective than methadone in some patients but it may increase the risk of opioid-related adverse effects.40

In a meta-analysis of 4 randomized trials, rates of heroin use and treatment retention with extended-release oral morphine were similar to those with methadone, but the trials were judged to be low to moderate in quality.41

Addition of supervised heroin injections to flexible-dose methadone therapy has been shown to improve treatment retention and may reduce criminal activity, incarceration rates, and social functioning, but it also increases the risk of adverse events.42

In a 12-week, randomized, double-blind trial in 196 patients with opioid use disorder, addition of the antitussive dextromethorphan 60 mg/day to methadone maintenance treatment significantly improved treatment retention and decreased plasma morphine levels compared to placebo, but addition of dextromethorphan 120 mg/day did not.43

In a 24-week randomized trial in 141 patients with opioid use disorder, addition of cognitive behavioral therapy to primary care-based maintenance treatment with buprenorphine did not improve rates of self-reported opioid use or opioid abstinence.44

PREGNANCY — Opioid use during pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of complications including preeclampsia, miscarriage, reduced fetal growth, fetal death, and premature delivery. Pregnant women with opioid use disorder should receive maintenance treatment with methadone or buprenorphine.45

Methadone has a long history of use in pregnancy and is generally considered the standard of care for maintenance treatment of pregnant women with opioid use disorder. More recently, buprenorphine has been used as an effective and safe alternative. In a randomized, double-blind, double-dummy trial in 175 pregnant women with opioid use disorder, neonates whose mothers were treated with buprenorphine during pregnancy required less morphine and had shorter durations of treatment for neonatal abstinence syndrome and shorter hospital stays than those whose mothers received methadone, but treatment retention was significantly greater among women taking methadone.46

Combination buprenorphine/naloxone products are considered safe for use during pregnancy, but data on their efficacy in pregnant women are limited.47

Data on the safety and efficacy of naltrexone use in pregnancy are also limited. In general, women taking naltrexone who become pregnant and are at high risk for relapse can continue treatment. Use of challenge doses of naltrexone to test for physiological opioid dependence is contraindicated because it can induce preterm labor and fetal distress.

LACTATION — Use of methadone or buprenorphine monotherapy by breastfeeding women is generally considered safe.2 Transfer of naltrexone through breast milk appears to be minimal, but clinical data are sparse.48

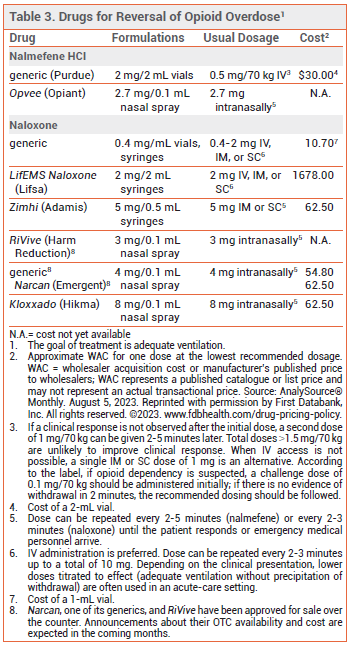

Two opioid antagonists, naloxone and nalmefene, are available for reversal of opioid overdose. The goal of treatment is adequate ventilation. If not already present, emergency medical services should be called immediately after administration of naloxone or nalmefene.

NALOXONE — Naloxone is the drug of choice for emergency treatment of opioid overdose. It is available in various dosage forms for intravenous, intramuscular, subcutaneous, or intranasal administration (see Table 3).49-51

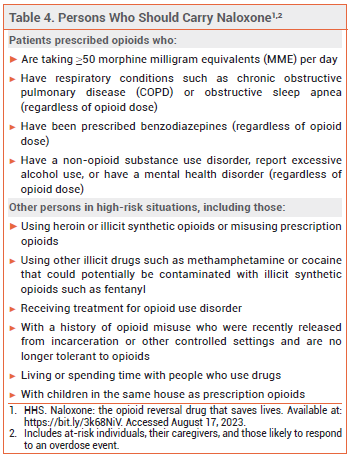

Availability – Every state in the US now has a naloxone access law; in most states, these laws grant both civil and criminal immunity to laypersons who administer naloxone.52 The US Department of Health and Human Services has recommended that certain individuals who are prescribed opioids or are at high risk for an opioid overdose, their caregivers, and persons who are likely to respond to an overdose event carry naloxone nasal spray (see Table 4).53

The FDA has approved the over-the-counter (OTC) sale of three naloxone nasal sprays (Narcan, one of its generics, and RiVive), but none of these products are currently available OTC. Announcements about their availability and cost are expected in the coming months.54,55

Pharmacology – Naloxone is a competitive mu-opioid receptor antagonist. In opioid overdose, it begins to reverse sedation, respiratory depression, and hypotension within 1-2 minutes after IV administration, 2-5 minutes after IM or SC administration, and 8-13 minutes after intranasal administration.

The half-life of naloxone (1 to 2 hours) is much shorter than that of most opioids; repeated administration may be necessary, especially for treatment of overdose with a long-acting opioid or an extended-release opioid formulation.56

Adverse Effects – Whether naloxone itself has any toxicity is unclear, but it can precipitate acute withdrawal symptoms in opioid-dependent patients. Acute opioid withdrawal is associated with anxiety, piloerection, yawning, sneezing, rhinorrhea, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal or muscle cramps, which are uncomfortable but generally not life-threatening, except in neonates. In a pharmacokinetic study, the most common adverse effects of intranasal naloxone were increased blood pressure, constipation, toothache, muscle spasms, musculoskeletal pain, headache, xeroderma, rhinalgia, and other intranasal effects including dryness, edema, congestion, and inflammation. Reversal of opioid overdose could unmask the sympathomimetic effects of stimulant drugs in cases of mixed overdose.

Pregnancy – No embryotoxic or teratogenic effects were observed with use of large doses of naloxone in pregnant mice and rats. Naloxone does cross the placenta, however, and may cause fetal opioid withdrawal or induce preterm labor.

NALMEFENE — The opioid antagonist nalmefene is FDA-approved as a nasal spray (Opvee) and an injectable solution for treatment of known or suspected opioid overdose.57,58 It has a longer duration of action than many opioid analgesics (half-life ~11 hours), and it could precipitate a period of withdrawal in patients dependent on opioids. Clinical data are lacking on use of nalmefene for reversal of overdose due to fentanyl or its analogs.

Availability – Nalmefene is only available by prescription. In most, but not all states, access laws that grant civil or criminal immunity to laypersons who administer naloxone appear to also apply to other opioid antagonists such as nalmefene.52

Adverse Effects – Adverse effects of nalmefene include nausea, vomiting, tachycardia, hypertension, fever, and dizziness. The nasal spray can also cause nasal discomfort and headache. Reversal of opioid overdose could unmask the sympathomimetic effects of stimulant drugs in cases of mixed overdose.

Pregnancy – No human data are available on use of nalmefene during pregnancy. Use of high doses of the drug in pregnant rats and rabbits did not result in embryotoxic effects.

- NIH. Drug overdose death rates. June 30, 2023. Available at: https://bit.ly/3rQyEmF. Accessed August 17, 2023.

- American Society of Addiction Medicine. The ASAM national practice guideline for the treatment of opioid use disorder: 2020 focused update. J Addict Med 2020; 14(2S Suppl 1):1. doi:10.1097/adm.0000000000000633

- Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of substance use disorders. Version 4.0 – 2021. Available at: https://bit.ly/3CkSSEp. Accessed August 17, 2023.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Medications for opioid use disorder. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) series 63 publication No. PEP21-02-01-002. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2021. Available at: https://bit.ly/3Yh7UYr. Accessed August 17, 2023.

- Canadian Research Initiative in Substance Misuse. CRISM national guideline for the clinical management of opioid use disorder. 2018. Available at: https://bit.ly/43X3GXf. Accessed August 17, 2023.

- Institute for Safe Medication Practices. Keeping patients safe from iatrogenic methadone overdoses. February 14, 2008. Available at: https://bit.ly/458otIl. Accessed August 17, 2023.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Emerging issues in the use of methadone. HHS publication No. (SMA) 09-4368. Substance abuse treatment advisory 2009. Available at: https://bit.ly/3QIgbD5. Accessed August 17, 2023.

- RP Mattick et al. Methadone maintenance therapy versus no opioid replacement therapy for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009; 3:CD002209. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd002209.pub2

- F Faggiano et al. Methadone maintenance at different dosages for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003; 3:CD002208. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd002208

- L Gowing et al. Oral substitution treatment of injecting opioid users for prevention of HIV infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011; 8:CD004145. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd004145.pub4

- S Nolan et al. The impact of methadone maintenance therapy on hepatitis C incidence among illicit drug users. Addiction 2014; 109:2053. doi:10.1111/add.12682

- T Santo Jr. et al. Association of opioid agonist treatment with all-cause mortality and specific causes of death among people with opioid dependence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2021; 78:979. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.0976

- L Lappalainen et al. Dose-response relationship between methadone dose and adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-positive people who use illicit opioids. Addiction 2015; 110:1330. doi:10.1111/add.12970

- L Sordo et al. Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ 2017; 357:j1550. doi:10.1136/bmj.j1550

- RL Woosley et al. QTdrugs list. Available at: www.crediblemeds.org. Accessed August 17, 2023.

- Inhibitors and inducers of CYP enzymes, P-glycoprotein, and other transporters. Med Lett Drugs Ther 2023 January 25 (epub). Available at: medicalletter.org/downloads/CYP_PGP_Tables.pdf.

- U.S. Government Publishing Office. 42 CFR 8.12 – Federal opioid treatment standards. October 1, 2002. Available at: https://bit.ly/45nY8Xz. Accessed August 17, 2023.

- LE Baxter Sr et al. Safe methadone induction and stabilization: report of an expert panel. J Addict Med 2013; 7:377. doi:10.1097/01.adm.0000435321.39251.d7

- Buprenorphine: an alternative to methadone. Med Lett Drugs Ther 2003; 45:13.

- In brief: Buprenorphine/naloxone (Zubsolv) for opioid dependence. Med Lett Drugs Ther 2013; 55:83.

- Bunavail: another buprenorphine/naloxone formulation for opioid dependence. Med Lett Drugs Ther 2015; 57:19.

- Once-weekly or once-monthly subcutaneous buprenorphine (Brixadi) for opioid use disorder. Med Lett Drugs Ther 2023; 65:133.

- Once-monthly subcutaneous buprenorphine (Sublocade) for opioid use disorder. Med Lett Drugs Ther 2018; 60:35.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Waiver elimination (MAT Act). June 7, 2023. Available at: https://bit.ly/3Q7YpZT. Accessed August 17, 2023.

- TV Parran et al. Long-term outcomes of office-based buprenorphine/naloxone maintenance therapy. Drug Alcohol Depend 2010; 106:56. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.07.013

- DP Kao et al. Arrhythmia associated with buprenorphine and methadone reported to the Food and Drug Administration. Addiction 2015; 110:1468. doi:10.1111/add.13013

- L Kohan et al. Buprenorphine management in the perioperative period: educational review and recommendations from a multisociety expert panel. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2021; 46:840. doi:10.1136/rapm-2021-103007

- DR Wesson and W Ling. The Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS). J Psychoactive Drugs 2003; 35:253. doi:10 .1080/02791072.2003.10400007

- S Ahmed et al. Microinduction of buprenorphine/naloxone: a review of the literature. Am J Addict 2021; 30:305. doi:10.1111/ajad.13135

- MK Greenwald et al. A neuropharmacological model to explain buprenorphine induction challenges. Ann Emerg Med 2022; 80:509. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2022.05.032

- Naltrexone (Vivitrol) – a once-monthly injection for alcoholism. Med Lett Drugs Ther 2006; 48:62.

- JD Lee et al. Extended-release naltrexone to prevent opioid relapse in criminal justice offenders. N Engl J Med 2016; 374:1232. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1505409

- E Krupitsky et al. Injectable extended-release naltrexone for opioid dependence: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre randomised trial. Lancet 2011; 377:1506. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(11)60358-9

- JD Lee et al. Comparative effectiveness of extended-release naltrexone versus buprenorphine-naloxone for opioid relapse prevention (X:BOT): a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2018; 391:309. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(17)32812-x

- L Tanum et al. Effectiveness of injectable extended-release naltrexone vs daily buprenorphine-naloxone for opioid dependence: a randomized clinical noninferiority trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2017; 74:1197. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.3206

- J Ma et al. Effects of medication-assisted treatment on mortality among opioids users: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry 2019; 24:1868. doi:10.1038/s41380-018-0094-5

- S Minozzi et al. Oral naltrexone maintenance treatment for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011; 4:CD001333. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd001333.pub4

- Y Adi et al. Oral naltrexone as a treatment for relapse prevention in formerly opioid-dependent drug users: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 2007; 11:iii. doi:10.3310/hta11060

- SD Comer et al. Depot naltrexone: long-lasting antagonism of the effects of heroin in humans. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002; 159:351. doi:10.1007/s002130100909

- M Ferri et al. Slow-release oral morphine as maintenance therapy for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 6:CD009879. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd009879.pub2

- J Klimas et al. Slow release oral morphine versus methadone for the treatment of opioid use disorder. BMJ Open 2019; 9:e025799. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025799

- M Ferri et al. Heroin maintenance for chronic heroin-dependent individuals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011; 12:CD003410. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd003410.pub4

- S-Y Lee et al. A placebo-controlled trial of dextromethorphan as an adjunct in opioid-dependent patients undergoing methadone maintenance treatment. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2015; 18:pyv008. doi:10.1093/ijnp/pyv008

- DA Fiellin et al. A randomized trial of cognitive behavioral therapy in primary care-based buprenorphine. Am J Med 2013; 126:74. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.07.005

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Evidence-based, whole-person care for pregnant people who have opioid use disorder. May 2023. Available at: https://bit.ly/4455IVk. Accessed August 17, 2023.

- HE Jones et al. Neonatal abstinence syndrome after methadone or buprenorphine exposure. N Engl J Med 2010; 363:2320. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1005359

- SL Wiegand et al. Buprenorphine and naloxone compared with methadone treatment in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2015; 125:363. doi:10.1097/aog.0000000000000640

- Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®) [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; 2006-. Naltrexone. Updated 2022 September 19. Available at: https://bit.ly/3OMJcw5. Accessed August 17, 2023.

- Zimhi – a higher-dose injectable naloxone for opioid overdose. Med Lett Drugs Ther 2022; 64:61.

- In brief: Higher-dose naloxone nasal spray (Kloxxado) for opioid overdose. Med Lett Drugs Ther 2021; 63:151.

- Naloxone (Narcan) nasal spray for opioid overdose. Med Lett Drugs Ther 2016; 58:1.

- Legislative Analysis and Public Policy Association. Naloxone: summary of state laws. February 3, 2023. Available at: https://bit.ly/3Kxgw7N. Accessed August 17, 2023.

- HHS. Naloxone: the opioid reversal drug that saves lives. Available at: https://bit.ly/3k68NiV. Accessed August 17, 2023.

- In brief: Over-the-counter Narcan nasal spray. Med Lett Drugs Ther 2023; 65:72.

- In brief: A new OTC naloxone nasal spray (RiVive). Med Lett Drugs Ther 2023 (in press).

- EW Boyer. Management of opioid analgesic overdose. N Engl J Med 2012; 367:146. doi:10.1056/nejmra1202561

- Nalmefene nasal spray (Opvee) for reversal of opioid overdose. Med Lett Drugs Ther 2023 (in press).

- Nalmefene returns for reversal of opioid overdose. Med Lett Drugs Ther 2022; 64:141.